“I just don't believe in the difference between high and low brow, between aristocracy and working class, between fine art and fine engineering” Ian Nairn

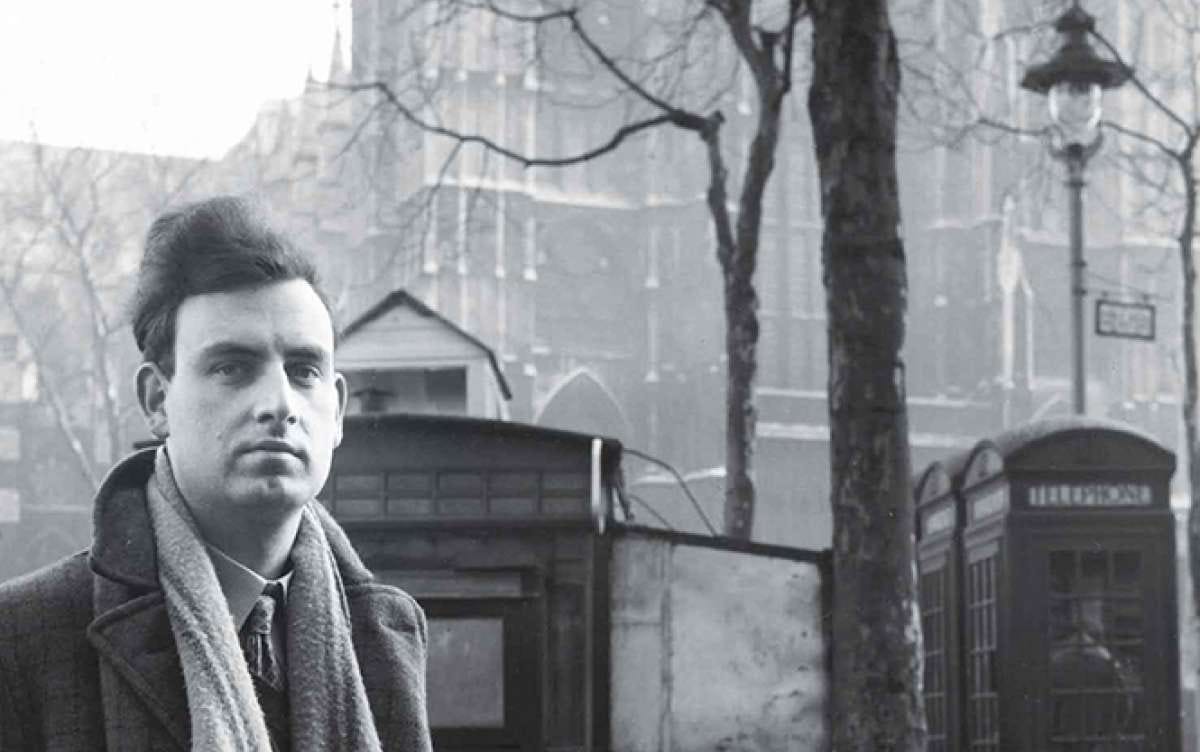

Ian Nairn, architectural critic, the father of Subtopian thought and one of the greatest and most important writers of his generation slaloms his way through a crowd of tanked up teenagers at Oktoberfest in 1970's Munich.

“This isn't a beer festival, it's a convulsion. I hope that most of the people here are genuine Munich not just tourists coming to watch a spectacle” he sneers to camera before a sudden rage overcomes him. He's apoplectic in his anger, visibly shaking and turning a worrying shade of purple, his hands wafting up and down as he tries to articulate his despair.

“It disgusts me and I'll probably get through more alcohol in a week than these bastards will in a year. This is. this is just for me, just animal”

He starts to lose composure completely now, his blood almost literally boiling.

“An expression of..'scuse me mate” he pauses briefly to toss aside a teenager who gets in front of camera like a child throwing a dolly onto a bed.

“An expression of collective Germanic force is fine, something that just happens to tourists cashing it. it hits me, IT HIT'S ME”

By the time he delivers the last lines, he's broken, almost in tears. The whole forty second segment of TV footage comes across like a cross between The Fast Show and the Bittersweet Symphony video.

I start with this description of footage not to lampoon or caricature Nairn in a bad light, (though it is a darkly funny piece of footage), but as an aid to explaining the balance of an incredibly complicated man. Within his anger are some interesting tells. Firstly, you can almost see where director Barry Bevin was going here. Two of Nairn's passions are travel and drinking, but to him the humble British pub wasn't just something to admire or write about, it was a place for shy and lonely man to sit in company and yet be completely alone. The pub was also, literally, his office. He would sit with pen and paper and, over a fag and pint, write some of the greatest books of architectural critique and guides ever recorded before handing them over to long suffering secretary Judith Gubbay (or wife Judy Perry) to be typed up properly. He didn't own a type writer, and this is how he worked before the waves of Watneys engulfed him completely. The 'more alcohol in a week' bit was no idle boast, he was a drinker. As Jonathon Meades rather pithily put it “Two weeks after I had met him, I returned to St George’s Tavern. (Nairn) was evidently on a regime. He drank only 11 pints”.

What is also telling, is the way Nairn brusquely slings aside the hapless young man who strolls into camera. This is one of times Nairn ever interacted with someone on film who wasn't the camera man. An incredibly shy and awkward man, he was blessed with an ability to convey to camera his thoughts, to ad-lib a cohesive and articulate case without notes or script, but the ability to interact with other humans was not in his remit. His only face to face interview on camera was for a film commissioned by the local council to promote Pimlico, where Nairn lived. His polite chit chat with a local doctor is painful to watch, Words literally dry up in his mouth as his normally forceful and forthright voice slows to a trickle and then nothing. It's even more agonising when one learns the GP being questioned is Nairn's actual doctor, a man he already knew.

Nairn was born in Bedford in 1930 before moving to Surrey in 1932. His first love was aircraft and after earning a degree in mathematics at Birmingham university fulfilled his ambition of becoming a fighter polite for the RAF. It was whilst stationed at Norfolk and without formal architectural qualifications that he started to write pieces on architecture for the Eastern Daily Press. After an avalanche of a letter campaign, he was permitted to write for the Architectural Review. At the age of 24 he wrote a special edition of AR called 'Outrage', The piece prophetised that "the end of Southampton will look like the beginning of Carlisle; the parts in between will look like the end of Carlisle or the beginning of Southampton". And to prove his claim he actually drove to both locations to take photos of the mirroring semi's, lampposts and telephone wires illustrating his point. He instantly became an enfant terrible of architectural criticism, coining the phrase 'subtopia', a term that hit instantly and hit hard. It was debated in parliament and thrust Nairn to instant fame. 'Outrage' set out the case against suburbia and the belief that the planners at the council had the peoples best intentions at heart. What started as optimism of what architecture turned into negativity and hopelessness. Within a decade he would be bemoaning modern design as "a soggy, shoddy mass of half-digested clichés". The new vision of town planning didn't just upset Nairn, it almost physically hurt him.

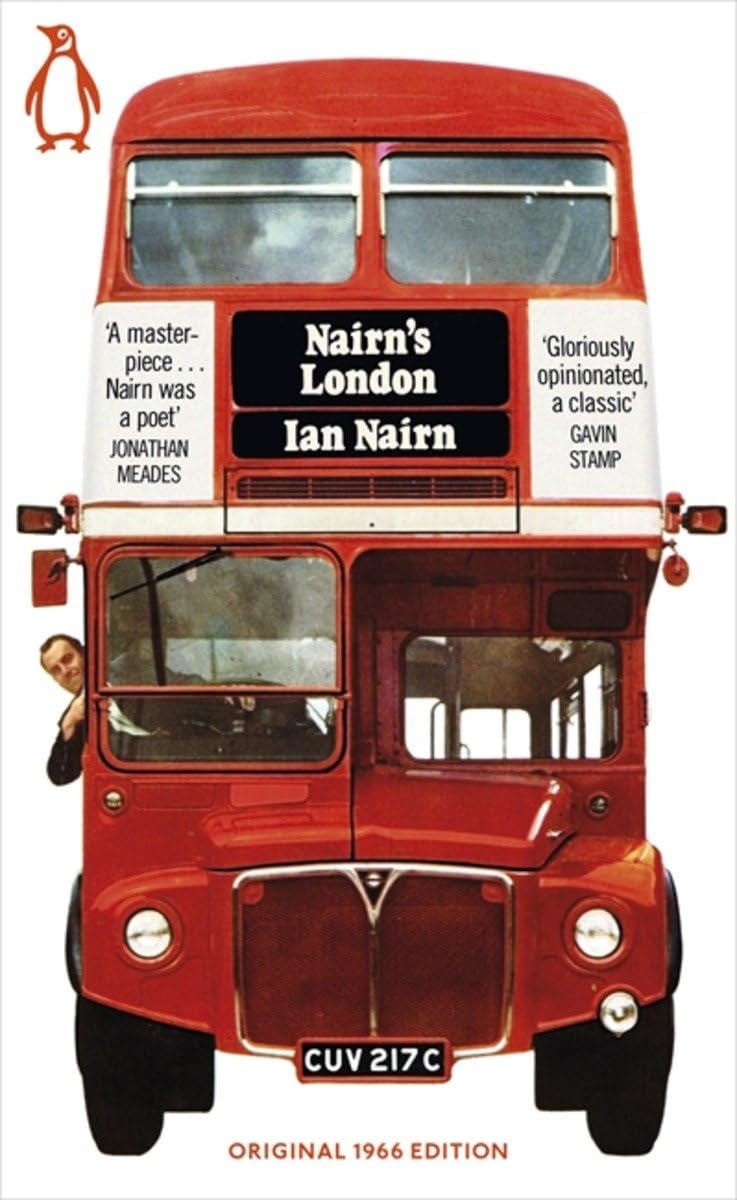

What happened just after he made that quote was a stroke of genius and to many Nairn's finest work. Published in 1966, Nairn's London was devised as kind of a guide book, it was sold in coin operated machines around London train and tube stations. But where in the past the guide book was dry and somewhat snooty, Nairn injected some much needed working class verve into the genre. Nairn's London is book designed to have the corners folded down, collect crumbs in the creases and sop up the odd spill of beer off the pub table, it positively looks nude without a tube or bus ticket used as a book mark. It's polemic, yet poetic, concerned not on what interests but what moves. It waxes lyrical not just on the obvious landmarks of the capitol but it's hidden churches, it's pubs, it's gasworks, hillsides and nooks. It is, inarguably, one of the finest books written about London.

The passion and articulation (at odds with the man drying up in front of his family doctor) positively pumps joy to the soul like the heart pumps blood. Of Lazenby Court he writes “Gas lamp above an evil stretch of red brick, you hardly dare turn the corner. And then, as suddenly as the switch in The Winters Tail, from tragedy to comedy the second half unrolls, a jolly passage with a comforting street at the end and a more than comforting pub”, St Mary-le strand is praised for 'The Portland Stone, half gleam half soot, has a fantastic range of textures, and to clean it would be like making over the face of a beautiful mature woman”. At the back of St Pancras station London 'for a moment-and just for a moment-seems fussy and flurried using two words when one will do. Anyone whose hear t was lost to bricky Leicestershire will find this almost unbearably nostalgic”. He describes churches in orgasmic terms “this building can only be described in terms of compelling, overwhelming passion. Why boggle, when there are a hundred ways of reaching god?”. Whilst Langford place (in possibly my favourite entry) is described as “A normal Saint John's Wood villa pickled in an embalming fluid by some mad doctor. The design radiates malevolence as unforgettably as Iago”.

________________________________________________________________________

My favourite Nairn work, however, is 1972's Nairn Across Britain. Recorded 11 years before his death, we find him in his final years of fight before the disappointment of losing the battles against the planners, the councils and the drink completely over take him. He's rather portly but pleasingly scruffy, a quiet fuck you to the television establishment but no less eloquent and positively brimming with civic pride. He comes across like a cross between Tony's Hancock and Wilson. The rage in Munich is a dying ember, and within three years he will be in a smashed church in Bolton in literal tears trying to come to terms with how someone could be so violent to something so beautiful (“it makes me ashamed to be part of the same branch of biology”). Within a decade the copious amount of pints will slowly take away his talent then quickly take away his life. Total defeat is close at hand, but here is one last hurrah of Nairn in his cups before the brain dead town planners destroy what he held so dear.

Even the title sequence of Nairn Across Britain is terrific. He strides from his Pimlico home to his Morris Minor to the soundtrack of Wade in the Water by Ramsey Lewis (a curious choice for programme about buildings and towns, as to me the song invokes a smoky inner city cellar), he strides like soul boy off to a nigher.

His presenting style is terrific. Unpolished, mainly unwritten, he talks almost directly to us. Not quite as articulate as his writing, no less thrilling. He travels not to the hip or vibrant towns but the butt of jokes on 70's Britain. One of the first port of calls is Northampton. He stands upon the top levels of The Emporium Arcade, a building whose fate is in the balance as the council wants tear it down due to having no architectural value. “No architectural value?!” he counters “with this great cupola here and the balconies? Arches with a perspective effect. And that in my experience, which with respect is rather larger than that of Northampton councillors is architecturally unique”. There's fight in the old dog alright, but even he concedes, gripping onto the staircase, that the future of the arcade is in the balance. “If they really do pull this place down it will be a diabolical shame”. The next shot, literally the next shot, after he says this is a caption saying 'Emporium Arcade demolished June 1972'. It's stings the heart of the viewer, but it must have been like a dagger going into Nairn's heart. You can almost see the rot setting in.

The next town to feel the Morris Minor's tyres is Stockport, where Nairn praises the local planning, but the heart sinks again as he drives through Manchester, with miles and miles of empty space where the slums were pulled down. “The Germans couldn't have done it, the town planners have” he sighs “did it have to be done this way?” He's right of course. The slums didn't have to be pulled down in one swoop rather than a “rolling program where you replace one street at a time”. He then stands above a Piccadilly Gardens which resembles Shrewsbury's Dingle. It's perhaps cheering that he hasn't seen what that has turned into.

He goes on through the country via Morris Minor, train and barge to wax lyrical about the Ribblehead Viaduct and the 'mushroom' pillars of Blackburn market, to do a piece to camera in a signal box (where despite himself he's as excited as a school boy) and sits on ghostly abandoned train stations, legs dangling off the platform as tries to come to terms with how the railway was decimated “Gone, all gone. It was odd in another way. Because for 100 years there was no road access. This place you just had to get to by rail”.

There is a great podcast chaired by Travis Elborough on Nairn, where one of the last things discussed was weather this man, this shy awkward lonely man, the working class outsider was humanitarian. But of course he is. Of course. Once you trot across the country with him it's clear that his argument is not about whether a building should be saved or not but the effect that it has on people, the people who live in towns being destroyed by planners. People who need houses, schools, libraries and light and deserve to live somewhere functional and pleasing to the eye. It wasn't that difficult for him envisage that, and surely his legacy should be that it's not impossible for us to fathom and demand either.

Nairn Across Britain is, thanks to Janet Street Porter of all people, is on the BBC Iplayer. Go enjoy it before it too goes forever.